| I’ll let the publisher do the speaking here:

In the fall of 1866, a twenty-year-old stenographer named Anna Snitkina applied for a position with a writer she idolized: Fyodor Dostoyevsky. A self-described “emancipated girl of the sixties,” Snitkina had come of age during Russia’s first feminist movement, and Dostoyevsky—a notorious radical turned acclaimed novelist—had impressed the young woman with his enlightened and visionary fiction.

Yet in person she found the writer “terribly unhappy, broken, tormented,” weakened by epilepsy, and yoked to a ruinous gambling addiction. Alarmed by his condition, Anna became his trusted first reader and confidante, then his wife, and finally his business manager—launching one of literature’s most turbulent and fascinating marriages.

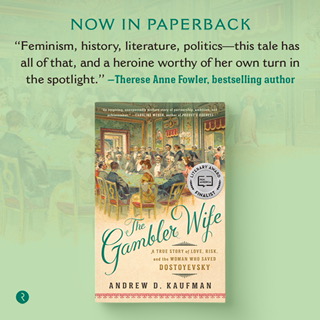

The Gambler Wife: A True Story of Love, Risk, and the Woman Who Saved Dostoyevsky, offers a fresh and captivating portrait of Anna Dostoyevskaya, who reversed her husband’s freefall and cleared the way for two of the most notable careers in Russian letters—her husband’s and her own.

Drawing on diaries, letters, and other little-known archival sources, Andrew Kaufman reveals how Anna warded off creditors, family members, and her greatest romantic rival, keeping their young family afloat through years of penury and exile. In a series of dramatic setpieces, we watch as she navigates the writer’s self-destructive binges in the casinos of Europe—even hazarding an audacious turn at roulette herself—until his addiction is conquered.

And, finally, we watch as Anna frees her husband from predatory publishers by founding her own publishing house, making Anna the first solo female publisher in Russian history.

The result is a story that challenges ideas of empowerment, sacrifice, and female agency in nineteenth-century Russia—and a welcome new appraisal of an indomitable woman whose legacy has been nearly lost to literary history.

***

Other recent blogs I’ve written about Russia that may be of interest:

Why Most Russians Still Love Putin

If Only Putin Had a Soul, Tolstoy Could Be the One To Save It. Here’s Why

***

Follow Books Behind Bars on Twitter and Facebook.

|