The Art of Swimming in the Great Sea of Sadness

Words have failed me in recent months. As a Jew and a human, I experience the horrific bloodshed in Israel as a firehose of tragedy so overwhelming that I can’t seem to catch my breath long enough to say anything meaningful at all.

Then there’s the ongoing tragedy in Ukraine, tame by comparison, as if that were even possible.

Against this geopolitical backdrop, I feel the approach of the holidays with a mixture of melancholy and anxiety. This time of year is tainted for me. On the day after Thanksgiving in 2018, my father died from a sudden fall while our extended family was vacationing together.

I feel like I’m swimming right now in the Great Sea of Sadness.

Not Swimming Alone

I know I’m not alone. Fellow swimmers abound. Some desperately flail their arms and legs in a bid to get somewhere, anywhere. Others hold their breath and close their eyes, floating in quiet despair. Others have calcified and stopped swimming altogether.

Then there are the blessed, who manage to find a steady rhythm. They breathe in and out, feel the cool water gently gliding along their skin. They trust in the purpose of all this pushing and pulling. They sense the beauty in the salty depths below. I pay close attention to these swimmers. I learn from them.

One of them is a friend of mine named Chris Farina, a Charlottesville filmmaker who made the documentary, Seats at the Table, about my Books Behind Bars program. A year and a half ago Chris was diagnosed with ALS, a neurodegenerative disease that affects the brain and spinal cord.

Sadness and Celebration

On November 5, the Charlottesville community came together to celebrate Chris at the Farina Film Festival. Snippets from each of his eight films were played, and introduced by the film subjects. There were a thousand people in the theater, including a former student of mine from Seats at the Table who’d made a special stop on her honeymoon trip from Savannah to Baltimore to be at the event.

Tears of sadness filled the space, but so did tears of gratitude and celebration. “Life is such a gift,” Chris spoke faintly from the stage in his wheelchair, flanked by his wife and two teenage children. His singular smile and spirit were as bright as ever, unmarred by the ventilator he now needs full-time. Chris is still working, making films, and sending me emails.

He is teaching me by example the art of swimming in the Great Sea of Sadness—one graceful, dignified stroke at a time.

I’ve been learning this lesson from another, unlikely source: a group of jail inmates who recently took my class on Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. It’s the story of a poverty-stricken, 23-year-old named Raskolnikov who, out of hopelessness and inner confusion, murders two people and then spends the rest of the novel wracked with guilt as he tries to unravel why he did what he did.

Raskolnikov never learned healthy outlets for his suffering. Alienated, angry, and humiliated by life, he killed to exert his power on the world. I hear versions of this story over and over again among the incarcerated students. One young inmate recounts how, in the moment when he pointed a sawed-off shotgun at a convenience store clerk, he felt a rare surge of power in his poverty-stricken life that meant far more to him than the money he stole.

A Different Approach

It’s a misguided approach to dealing with feelings of powerlessness. Many jail students know it and want to get off this dysfunctional path. They want to end the cycle of trauma and brokenness that has defined their lives.

They want to love and be loved. They are reclaiming their power by making new choices, by caring for themselves and one another.

There’s beauty alongside the brokenness in that jail classroom. Inmates bear witness to one another’s hard stories, a tight-knit community of tears. Jail students console a grief-stricken friend who’d lost his newborn during childbirth, an event he wasn’t permitted to attend. An inmate sheds his tough-guy persona to hug another who speaks of his deep love for his young boys, whom he won’t see for thirty years.

Without a whiff of envy, the incarcerated students celebrate a friend who will soon be released.

They hope.

They’re learning how to stop flailing their arms and hardening their hearts and instead swim steadily through the salty water, one intentional, graceful stroke at a time.

Let’s join them, and Chris, and keep swimming together.

***

Connect with Dr. Kaufman on Amazon, Twitter, Facebook, his private FB Group, Linked In, Instagram, Goodreads, and YouTube, and sign up for his newsletter here.

Follow Books Behind Bars on Twitter and Facebook.

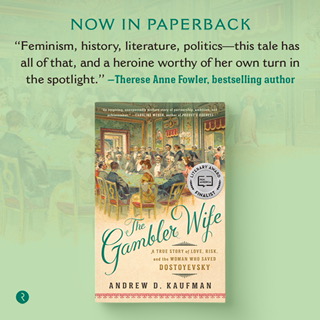

Order The Gambler Wife: A True Story of Love, Risk, and the Woman Who Saved Dostoyevsky

A PEN/America finalist, now optioned for film!

This is a beautiful essay. I love how you explain Raskolnikov. Crime and Punishment was assigned in my very first college class, Introduction to Literature, which was years ago. I can see how your students would identify with Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov, who suffers guilt and sadness for such a long time. A Great Sea of Sadness is a wonderful way to describe your students’, friends’ and your own experiences with grief. I’m glad I found your blog.

Thank you very much, Kay. I, too, am glad we found each other. I very much appreciate your engagement with Dostoyevsky’s ideas and joining me on the art of swimming in the great sea of sadness.