Dostoyevsky on the Importance of Community. How to Create It in the Classroom

Creating community in the classroom has been crucial this past year, particularly at the university level. We should be thankful for all the ways that we’ve been able to remain in contact over the last 18 months, even if they aren’t ideal. From Zoom calls to masking to social distancing, we’ve done our best to keep that sense of community together, despite the restrictions necessary to fight this terrible virus.

Yet it’s also been a constant reminder of all that we’ve lost and that those communal interactions are so essential, even if they take extra effort these days.

As an educator, I think about this often, especially in the current environment, and strive to create a classroom community that overcomes the divisiveness and isolation felt by so many students.

Lessons From the Classroom

I’m reminded of the final days of one of my Books Behind Bars classes, in which my university students meet regularly with students at Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center to discuss big life questions—Who am I? Why am I here? How should I live?—through the lens of Russian literature.

Our last meeting with correctional center students had taken place a few days earlier, and it was the final opportunity for the university students and me to say goodbye to one another. We sat around a large table and looked at one another with anticipation. One student expressed the gratitude she felt toward her classmates for the lifelong relationships she formed this semester. Another student spoke of the correctional center residents whom she’s come to love and whom she fears she might never meet again.

I tried to express to my students what this class meant to me, what they have meant to me. I invite them to remember this connection we are all feeling and to always keep this memory tucked away for future occasions when they are overwhelmed by busyness, or emptiness, or the discordant voices of cynics trying to convince them to give up on their idealism.

“That’s what this class is all about,” I say. “That’s what education is all about.”

Learning from Dostoyevsky

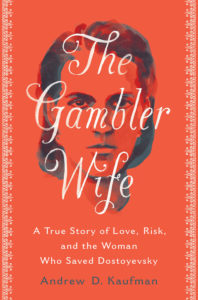

Not surprisingly, I draw my inspiration for the classroom, in part, from the Russian literature I teach, and particularly from the works of Dostoyevsky, who figures prominently in the book I’ve spent the better part of the last decade working on: The Gambler Wife: A True Story of Love, Risk, and the Woman Who Saved Dostoyevsky. In this challenging era, it’s easy to compare ourselves to the Russia of Dostoyevsky’s time, which witnessed the breakdown of community ties and had lost its moral bearings. Dostoyevsky provided his nineteenth-century readers a path out of this morass that educators in our own time would do well to heed.

In The Brothers Karamazov, the character of Alyosha, though not a teacher in the strictly professional sense, understands something vital that I, as an educator, try to take to heart. He understands instinctively that one authentic conversation, one gesture of kindness, one expression of love on the part of a teacher has the power to change the trajectory of a young person’s life.

He understands, too, the importance of withholding judgment and of radical humility before one’s fellow human being, thereby putting into practice the wisdom contained in the words of his late mentor, the famed Father Zosima, who said, “the moment you make yourself sincerely responsible for everything and everyone, you will at once understand that…it is you who are guilty on behalf of all and all.”

The Brothers Karamazov, in fact, demonstrates what can happen to a society that loses touch with this imperative. Nowhere is this more evident, Dostoyevsky believed, than in the functioning of the courts, where questions of human guilt and innocence are decided every day. According to the jury who listened to the case of the Karamazov murder, the facts and rational deductions to be made from them pointed to one conclusion and one conclusion only: that Dmitry was guilty of parricide. And yet, he didn’t do it.

This gross miscarriage of justice that will cost Dmitry decades of his life stemmed from the same faulty thinking, Dostoyevsky believed, that leads society to privilege punishment over pity. Relying exclusively on logical, left-brain thinking to find the truth and pronounce judgment about human guilt and innocence is fundamentally flawed.

Such a society is made up of individuals unable to see the motes in their own eyes, unwilling to accept their collective guilt and shared responsibility for the fates of all members of the community.

Inspiring Classroom Students to Take a Different Path

Abraham Lincoln said that “the philosophy of the schoolroom in one generation will be the philosophy of government in the next.” This insight has forced me to think hard about the kind of society I’m modeling for my students in my classroom.

I ask myself: What are we as educators doing to make sure we rectify these mistakes for the next generation? What are the classrooms of today modeling for our students? How are we better able to form a lasting community?

In The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky shows us the troubled society of his times and, through Alyosha, how a teacher can inspire his students to follow a different path. Wherever it may lead, that path, Dostoyevsky believed and I agree, must start from a place of love.

For, as Father Zosima says, “everything, like an ocean, everything flows and comes into contact. You touch in one place and at the other end of the world it reverberates.”

Let’s not forget that as we do our best to keep a sense of classroom and outside community alive, even when outside forces make it harder to do so.

***

Connect with Dr. Kaufman on Amazon, Twitter, Facebook, his private FB Group, Linked In, Instagram, Goodreads, and YouTube, and sign up for his newsletter here.

Mailing List

To receive monthly articles, inspiration, and updates, including updates about Andy's new book, The Gambler Wife: A True Story of Love, Risk, and the Woman Who Saved Dostoyevsky, please fill out the form below.

interesting post

Thank you. It reflects a lot of my current thinking about teaching and Dostoyevsky’s wisdom, which he is rarely given credit for.

You’re very welcome, and thank you for sharing. I agree that there’s a lot of wisdom in Dostoyevsky’s prose that he is often not given credit for. It’s just often harder to find than the wisdom contained within Tolstoy’s writings.