How I Found My Voice and Myself in War and Peace

At a book talk I gave a few years ago, a teenage boy in the audience, intrigued by the stories I’d been telling about young characters’ tortuous journeys in War and Peace, asked me a question during the Q&A. “Did Tolstoy, like, really experience all that?”

At a book talk I gave a few years ago, a teenage boy in the audience, intrigued by the stories I’d been telling about young characters’ tortuous journeys in War and Peace, asked me a question during the Q&A. “Did Tolstoy, like, really experience all that?”

The ingenuous question got me thinking, not only about Tolstoy’s writing but my own. And it inspired me to share something I hadn’t quite articulated before in public.

Writing a Book on War and Peace

The hardest part of writing a book about War and Peace, I told him, wasn’t all those years spent researching the topic, or mastering something writers fancily refer to as “craft.” No, the most difficult part was making sure I was telling the truth—about Tolstoy, and about myself.

How could I share Tolstoy’s wisdom about happiness if I didn’t know my own views on the subject? How could I talk about what love and death and courage mean to Tolstoy without knowing what those things meant to me? That would be like trying to describe to others a magnificent landscape I’d observed while looking through a dirty window or sharing the beauty of a concert I’d listened to with ear muffs on.

No, this would not do: to hear Tolstoy’s voice, I first had to hear my own.

Easier said than done. The process has taken me decades. You see, I grew up in a house filled less with the aroma of, say, apple pie baking in the oven, than the sharp rot of first editions in our countless bookshelves competing with the sweeter scent of the latest new novels and biographies.

From a relatively young age, I learned how to talk about experiences, without actually, well, experiencing them.

The many paintings and sculptures I was not to touch sometimes gave me the impression that I was a visitor in a precious art gallery—always at a safe and admiring distance from Beauty and Truth, but never close enough to fully engage or create them.

Finding Myself First

As an aspiring seven-year-old actor, I was often so scared to perform in front of people that I’d hide under a table or behind a wall and recite my lines while squinting and covering my ears for fear someone might catch me making mistakes. As I look back on my decision to pursue a doctorate in Russian literature, I think I chose that path in part because it was a more socially acceptable way to satisfy my deepest creative urges.

I could analyze and admire all those writers from a safe distance, without ever taking the risk of actually trying to be one myself.

I’ve always found it puzzling that, as someone who’s dedicated his life to the study of literature, I still tend to read more nonfiction than fiction: analysis of the real world has always felt safer than losing myself in a fictional one. A graduate school professor gently admonished me once in his thick Russian accent: “You know Andy, as scholars, we must throw our emotions out the window.”

That was easy advice for me to follow.

My writing in those days was cautious and distant. My doctoral dissertation sounded rather like an out of tune trombone with a dirty sock stuffed in the barrel. There was something, I sensed at the time, bubbling beneath the surface of all that abstraction and studied precision, but I didn’t quite know what. My voice was buried. My life was buried. I was a mess, professionally and personally.

So I bolted—from academia, from my family, from the intellectual life, from Russian literature, from anybody or anything I believed to be the source of inability to be me—and pursued what I saw then as a promising career as an actor. I moved to Hollywood, grew my hair long, put on forty pounds, estranged myself for a time from my family and friends, and didn’t read a word of Russian literature for about two years.

I did read books with the word “passion” in the title, like A Dream of Passion or How to Find Your Passion. Passion, you see, was where it was at for me in those days. I exuded it everywhere: on the stage, in the grocery store, on the streets of Las Vegas, whereas part of my self-imposed creative boot camp I tasked myself with the challenge of dancing and singing and reciting Russian poetry atop garbage cans on the Vegas strip on Saturday evenings.

I wasn’t the first lost soul who’d come to Tinseltown, or Las Vegas, searching for something missing in his life, and I wouldn’t be the last. But I may have been one of the very few with a Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures. That, at any rate, was the one (and often the only) thing about me that stuck in peoples’ minds after my over-the-top, yet unmemorable auditions.

As I sauntered along Hollywood Boulevard, I conjured up images of Hemingway or Fitzgerald strolling along the Champs-Élysées in Paris in the 1920s. In those few moments when I got around to actually putting fingers to the keyboard, my writing was brilliant—or so it seemed to me in that exhilarating, self-enclosed world I’d created for myself. In reality, my prose rang roughly as false in that heady period as it had before my grand Hollywood escapade.

If my dissertation was emotionally muffled, my Hollywood writing was loud and monotone, overly eager to be something it was not.

Finding My Voice

I eventually returned to academia, initially with my tail between my legs, thinking I’d failed at my attempt at a creative life, and later with a steadier gait, as the quieter rhythms of ordinary everyday life in Virginia soothed my bruised spirit. I also returned to and radically rewrote my dissertation, eventually turning it into a book, which still had vestiges of the obedient graduate student writer I once was. But it wasn’t all bad. Something like my own voice was beginning to emerge.

“If you want to work on your art,” Chekhov used to tell beginning writers, “work on your life.”

And that’s what I did. It wasn’t an easy process. I had to dig deep in the dirt, sift well through the dross of my failures, false steps, and illusions in order to discover even the smallest nuggets of truth I could call my own. I got married, had a child, and my family went through a financial crisis—a series of events that catapulted me into one of the more creative periods of my life up to that point.

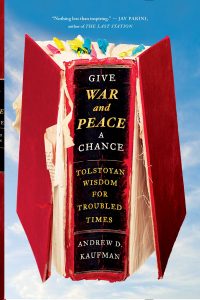

And I wrote another book—about Tolstoy’s War and Peace, which, I argued, is the classic for our time.

It’s about people searching for meaning and stability in a world being turned upside down by the forces of war, social change, and spiritual confusion. Of course, it’s a book about my own inner journey as well.

And here’s the interesting thing: Those starts and stops, radical shifts in direction, that toggling between fearfulness and furious passion—all of it was essential to the creation of that book. The very tone of the book, I can now hear, shifts between youthful exuberance when I describe Natasha’s wild dancing or bumbling, bespectacled Pierre’s innocent openness to the world, to a more sober tone later in the book when I write about family and death, and perseverance.

Most of the characters I focus on are in their teens and twenties when the book opens, and a decade and a half older at the end. It’s telling that one of the first chapters I wrote was called “Imagination,” and the final chapter is called “Truth.”

None of this is to suggest that I’ve finally discovered my voice completely. One’s voice is continually evolving. Four years later, with a second and well into my next book—this one about Dostoevsky—I can say I’ve reached a point where the artist and the intellectual have finally called a truce, and are working together. The cautious, reserved Stanford grad student and the Hollywood kid desperate to be heard have found a middle ground, where passion and prudence can peacefully coexist.

My prose has become more fully integrated than ever before, and it finally feels like it was written by someone I truly recognize.

*****

Thanks so much for dropping by and reading what I have to share today. I appreciate your interest. If you think any of your friends would be interested in today’s blog post, use the share buttons below to share with them. If you enjoyed today’s blog post, click here to join my group of readers. I send out monthly newsletters and would never spam you….

[…] The graduate students, myself included, dutifully nodded, of course, for we were in no position to challenge this man’s authority; what’s more, we recognized in his response an all too familiar refrain we’d been hearing over and over since our college days: Work hard, rack up the right credentials, jump through the right hoops, meet the right people, eventually publish in the right journals, and—voila!—academic success can be yours. But to what end? And at what cost? […]