What Are We Really Teaching Our Kids?

I published this article in Inside Higher Ed in September 2020. Even though it addresses the crisis in education brought about by both COVID and the George Floyd tragedy, its message seems highly relevant to our current climate, as well: What or why to teach are more important considerations than how to teach if we are to offer an education that truly matters at this distinct historical juncture.

“Democracy has to be born anew every generation and education is its midwife,” wrote the educational philosopher John Dewey in his classic work School and Society. The perfect storm created by the COVID-19 pandemic and George Floyd’s tragic death and its aftermath has offered an unusual opportunity to renew our democracy in the place where it can have far-reaching impact: inside our nation’s classrooms.

But that will happen only if professors and administrators resist the temptation to dwell on the question of how to teach online and focus instead on a more challenging and ultimately deeper question:

What is teaching for in our time of trauma?

Now more than ever, college instructors need to stop thinking of themselves as purveyors of expert knowledge and start to play the role of facilitators of human learning and personal growth for their students. To some, that might seem obvious. Yet such an approach represents a sea change in how many college educators still think about teaching and learning.

A Sea Change in Teaching and Learning

A while back, I sat on a task force to make recommendations for teaching at an American academic institution. Many of the classes I visited were stimulating and taught by caring and popular professors. But few of them encouraged the deeper learning needed to sustain our education system or revitalize our democracy in this unique moment.

I saw rows of students passively receiving facts, figures, and concepts delivered by the expert in the front of the room. I observed tests demanding recall and regurgitation, not reflection or the creation of new knowledge. I read elegantly laid-out course syllabi with their lists of requirements and explanations of grading policy, giving the impression that knowledge is orderly and fixed and that learning can be measured by a point system.

Aside from the laptops and cellphones scattered about or the giant screens at the front of the room, the classrooms I visited looked pretty much the way they did a half-century ago.

All that abruptly changed in mid-March, 2020 when the pandemic forced college instructors everywhere to abandon face-to-face teaching and transition their courses online with barely a week’s notice. I was teaching a class called Books Behind Bars, where my University of Virginia students meet regularly with committed youth at Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center to explore questions of meaning, value, and social justice through conversations about Russian literature.

Moving online was a serious blow to this class, the core of which is the powerful relationships that form between the two groups of students. And so I took crash courses in Zoom and other online tools and consulted every resource I could get my hands on, desperately hoping I could set up virtual meetings between the two groups. Then COVID struck at the correctional center, infecting an eighth of the incarcerated youth population. Facility-wide medical lockdown ensued, and any hope of resurrecting the relationships between the two groups of students vanished. My class as I knew it was dead.

And that’s when my real education began.

What It Means to Be Human

Suddenly, my frantic attempt to master the art of online teaching seemed irrelevant. The real issue facing me wasn’t how I would transition my course online but rather what my class was about now that the world we knew just a few weeks earlier no longer existed.

What my students needed from me at this moment was not my expertise or excellence in virtual course delivery but my honest admission that I’d never been here before and the reassurance that we would figure this out together.

And yet my temptation to do the exact opposite — to seek tips and tricks of online teaching to maintain some semblance of control over the chaos surrounding me — was powerful indeed. But the pandemic was still more powerful and became the inevitable backdrop of nearly everything we did and talked about. My students and I were engaged in a struggle to make meaning out of what seemed like a meaningless situation.

The questions deep in our hearts were not about Russian literature but about what it means to be human at a time like this. Once again, the so-called accursed questions of Russian literature — Who am I? How should I live? Why am I here? — took center stage in the class, and my job was to support students in finding their own answers.

And find them they did — not so much in words as actions.

Students took inspiration from examples of others expressing their deepest humanity in profound ways: the front-line health-care workers who chose to wake up every day, go to work, and risk their lives to save others; furloughed employees who refocused energies on their families and communities; thousands performing #TogetherAtHome concerts reminding us all that the opportunity to create beauty and connection is present even in the darkest times.

My university students created videos of themselves sharing personal reactions to the literature as if the correctional center students were still sitting there with them. They wrote poignant letters to their Bon Air partners they knew they would never see again. They channeled their sadness into a social action project to raise awareness of the plight of correctional center residents who suffered the ravages of COVID at disproportionately higher levels than they and their fellow students.

The students undertook these projects amid their anxieties, fears, and responsibilities while finishing a tumultuous semester. They watched the catastrophic toll on human life, even as they themselves were traumatized and faced significant challenges. Some students were living at home in dysfunctional relationships with their families. Others had connectivity issues, preventing them from finishing the semester. Still, others were scrambling to find work just to stay afloat.

No wonder academic learning wasn’t their top priority. Nor should it have been. Books Behind Bars had become a class on resilience, compassion, and creativity in a time of national trauma. I grew far less interested in what my students would remember in five years about the course content than what life lessons they would take with them.

A Rare Teaching Opportunity

I’ve spoken to many faculty members whose courses had similarly taken on new meanings and heightened urgency amid the pandemic. A colleague who was teaching a seminar on leadership watched his course transition overnight into an experiential learning class on how to lead well and live wisely in troubled times. Another colleague, a religion professor, was teaching a class on the Jewish Haggadah, a beloved text that Jews read on Passover to recount the story of the 40-year exodus from Egypt. During lockdown, students were learning one of the Haggadah’s most enduring lessons: how to create meaning, uphold ritual and maintain a sense of community when the past is gone and we are left wandering in existential limbo.

As professors gear up for the current academic year, they will find no shortage of tricks and tips for delivering an effective online course. Almost anybody can get pretty good at it with enough time and practice. But the online teaching gurus with their treasure trove of advice and resources are not what we need most now. They can help us figure out how to teach, but not what to teach or why to teach, which are more important considerations if we are to offer an education that truly matters at this distinct historical juncture.

Administrators have been working around the clock to determine what campuses and classrooms will look like this year — whether classes will be face-to-face, remain online, or be a hybrid. But all of that planning will amount to little if the basic assumptions about what teaching is for remain the same as they were in the early part of 2020. If that happens, then we will have squandered a rare opportunity.

It’s time to do away with rows of desks or faces on a computer screen — where students passively scribble down somebody else’s report on knowledge. Whether meeting face-to-face or virtually, students should be invited to co-create knowledge, test their insights out in the world, and grapple in a profound and personal way with what it means to be human in our troubled times.

***

Connect with Dr. Kaufman on Amazon, Twitter, Facebook, his private FB Group, Linked In, Instagram, Goodreads, and YouTube, and sign up for his newsletter here.

Follow Books Behind Bars on Twitter and Facebook.

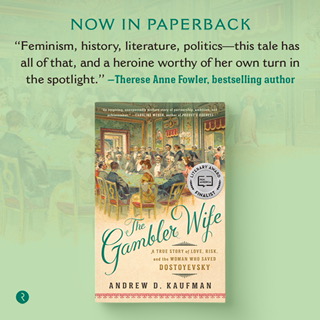

Order The Gambler Wife: A True Story of Love, Risk, and the Woman Who Saved Dostoyevsky

A PEN/America finalist, now optioned for film!