Compassion and Humility Must Lead the Way to Criminal Justice Reform

I was recently invited by the Good Men Project to respond to a reader who asked a question as part of their Ask an Ally column, where people wanting to be better allies pose an anonymous question about a social justice issue. Here is the question that was asked, and then my response, which was originally published by The Good Men Project here.

“I consider myself an ally and I want to get behind the social justice movement in any way I can, but I draw the line at including felons as “oppressed”. While I understand that our justice system is inherently racist. I don’t think it is fair to lump the rights of formerly incarcerated people in with those with mental health issues, POC, LGBTQ+, people with disabilities, and women for the obvious reason of personal choice.

None of these other groups are experiencing oppression because of a choice they made, so why are we supposed to fight for the rights of those who knowingly broke the law?”

The question you raise is an important one. The problem with so many discussions about criminal justice reform is that people tend to embrace ideological extremes. I’ve spent the past twelve years working with incarcerated youth and adults who participate in my Books Behind Bars program.

In this program, university students and incarcerated individuals meet to explore questions of meaning, value, and social justice through conversations about Russian literature. This experience has led to me an awareness of the irreducible complexity of crime and the people who engage in it.

I’ve met people from all sorts of backgrounds who commit all sorts of crimes for all sorts of reasons: I worked with an eighteen-year-old kid whose parents were incarcerated, and he had the responsibility of taking care of his younger siblings, so he robbed a convenience store at gunpoint to get some needed cash. I met a young man who nearly murdered a woman as part of an initiation into a gang, the only real family he ever knew. I got to know a drug addict who’d never received the medical help he needed and was in and out of prison most of his adult life. I taught a smart, charming kid from an upper-class suburban family who raped a girl for reasons I still can’t comprehend.

The Complexity of Crime

What I’ve learned from these encounters is that crime is the product of an exceptionally complex concatenation of personal, social, and environmental factors that cannot be reduced to any easy explanation.

To say that “these people made a choice,” simplifies such complexity. It also overlooks the fact that some people have fewer options to choose from in the first place.

Minoritized populations and especially people of color are disproportionately represented in our criminal justice system. This isn’t because they make more bad choices than Whites. Rather, as Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, has shown, it’s because they have never had the same access as Whites to economic and social opportunity, to equal protection under the law, or to fair sentencing procedures. People of color receive harsher and longer sentences for less severe crimes than their White counterparts, and they are wrongfully convicted at a far greater rate.

Do you remember the famous Central Park Five case? In 1989, five teenage boys of color were wrongfully imprisoned for the brutal attack on a jogger in Central Park. Only in 2002, after many of them had spent thirteen years behind bars, did DNA testing and a confession by the real attacker, reveal that the boys didn’t do it.

The reason so many people believed they did at the time is that their conviction fit into a narrative about a growing national epidemic of dangerous young Black men (called “super-predators” in the 1990s) who needed to be stopped. Though the epidemic was later shown to be an illusion, and the term “super-predator” recanted by the person who coined it, the racist thinking that gave rise to that illusion and that word is still alive and well at every level of our criminal justice system.

Oppression, then, can take many hidden forms. To say that some people are “oppressed” because of a mental illness or sexual orientation whereas incarcerated people are not because of a choice they made fails to take into account this systemic reality.

Embracing Our Shared Humanity

Given this, I’d like to suggest that our orientation towards incarcerated people and criminal justice reform in general needs to change. Let’s for a moment focus less on what to do about the offenders and more on what do about our own attitudes toward them.

Social change begins with mindset change. And mindset change requires that we cultivate radical humility, reminding ourselves of Jesus’ injunction: “Do not judge lest you be judged. For in the way you judge, you will be judged; and by your standard of measure, it will be measured to you.”

Books Behind Bars teaches students (from both groups of students) to embrace the full-blooded humanity of one another. At the beginning of the semester, both the university and correctional center students come in with assumptions and stereotypes. In time, through deep conversation and their growing relationship with one another, students develop a much more complex, nuanced, and charitable view of one another.

“I was expecting them to come in here and be scared or look down on us, thinking they’re criminals,” said one correctional center resident about the university students. “I didn’t expect for us to be able to connect our lives…We had to struggle with the same problems.” A university student admitted: “I learned that I’m not free of stereotyping. My image of a correctional center resident was a black person, somebody who is ‘off’ and doesn’t want to be messed with or talked to or doesn’t want to talk about anything intellectual…I am so proud of the residents for proving me wrong.”

When I watch these two groups of students sitting down side by side each week, and taking the risk of sharing their most intimate human stories—about love, about loss, about their search for meaning—I am inspired. I think: This is the kind of society I want to live in, one in which people from radically different backgrounds can come together, overcome barriers, and communicate in an authentic and open way about life’s most important questions.

Conversations in Books Behind Bars aren’t often comfortable. Students passionately disagree with one another. But these disagreements don’t devolve into ideological screaming matches, because participants see in one another not a political or ideological enemy, but a fellow human being struggling with the same fundamental challenges.

What if democracy functioned like this? This would be a democracy rooted in the ethos of love and respect for the dignity of every person. Without this foundation, little else matters. How can we ever hope to have civil discourse or move forward as a society if we dehumanize others? And passing easy judgment on who deserves mercy and who doesn’t can itself be an unintended form of dehumanization.

For it says: I know who is oppressed and who isn’t, whose circumstances justify their decisions to steal, rape, or murder, and whose do not. It arrogates to the person doing the judging a superiority and knowledge that none of us truly has.

There are often deeper, hidden social realities at work, as well as truths about the human personality that elude such absolute categories.

“Man is flowing”

I had a university student who learned this lesson in an unexpected way. She spent the whole semester resisting the urge to find out what her resident partners did to wind up at the correctional center. Then, a few days before the end of the semester, she couldn’t hold out any longer. She needed to know, so she looked it up online and found out that one of her favorite residents had murdered someone.

This brilliant, charming young man—a guy she admired, with whom she’d shared intimate human stories, whom she considered a friend and would’ve invited into her own home to meet her family—had snuffed out another person’s life. Just like that. “I had to share this with you,” the student confessed to her fellow university students through tears.

I myself was floored, not knowing how to respond—all the more so because this bombshell revelation came in the last twenty minutes of the very last class of the semester. This was a time when I planned to bring the ship of the class safely into port, just as I’d been doing for years.

I was seized by a moment of self-doubt. Maybe, I thought, I’d been leading the university students down a pollyannaish path all these years. Maybe I’d made them believe that these guys are all basically good people who made a bad decision, or were in the wrong place at the wrong time, or just had the misfortunate of being born on the wrong side of the tracks.

All of that is true. But it’s not the whole truth. What, then, was the larger truth? As I sat there wracking my brains, a long uncomfortable silence filled the room…

All of a sudden, Tolstoy’s words came to me: “Man is flowing. In him are all possibilities: He was stupid, now he is clever; he was evil, now he is good, and the other way around. In this is the greatness of man.”

And it hit me: We must open our hearts and minds to such a degree that we can hold all these opposites in our consciousness at the same time. “You don’t need to come away from this experience looking at the guys as all good,” I said to the group. “Nor do I want you to come away looking at them as all bad. Look at them as people: complex, flowing, as capable of evil as virtue, full of beauty and ugliness, like all of us. That’s the deepest message of this class. That’s the deepest message of Russian literature itself.”

Every one of us is flawed and flowing. We have all been traumatized by life in one way or another. For some, like people of color, that trauma is built into the very fabric of our society. We are all the product of an incredibly complex web of environmental influences and circumstances that afford some people more choices and some people fewer. What we share, however, is our fundamental humanity.

We are interconnected within a great labyrinth of linkages, my fate intertwined with yours and yours with mine, whether we realize it or not. Given this, compassion and humility are our surest guides and the one true way forward as a society.

For, as Dostoyevsky said, “Everything, like an ocean, everything flows and comes into contact. You touch in one place, and at the other end of the world it reverberates.”

***

I’d love to connect with you on Twitter, Facebook, my private FB Group, Linked In, Instagram, Goodreads, YouTube, and Amazon, and sign up for my newsletter here.

Follow Books Behind Bars on Twitter and Facebook.

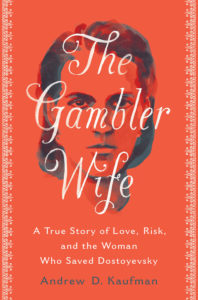

Order The Gambler Wife: A True Story of Love, Risk, and the Woman Who Saved Dostoyevsky, Finalist for the 2022 PEN America Literary Award in Biography