Why Most Russians Still Love Putin

I’m often asked how Russian literature of the past can help illuminate Russian politics today. I recently wrote an article on this very subject and received a number of follow-up questions. One of the most interesting of them was: Why is Putin still so popular in Russia despite the world’s response to his war and the sanctions crippling his country’s economy?

There’s an explanation for this. Though his veil of invincibility has recently been pierced by Ukrainian successes on the battlefield and growing dissent at home, don’t underestimate the hold Putin’s rhetoric still has on the Russian imagination. The nationalist rhetoric he has used to justify the war in Ukraine resonates deeply in a country that lived through great political and spiritual turmoil following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. After the tragedies of 20th-century Russian history, and the humiliations of the past 30 years, in particular, many ordinary Russians are seeking unequivocal proof of their national worthiness—indeed superiority—among the family of nations. And Putin has delivered.

Censorship, misinformation, and the threat of imprisonment don’t fully account for why merely tens of thousands of Russians have protested the war in Ukraine, rather than hundreds of thousands, as happened, for instance, during the Russian Revolution of 1917, when countless Russians took to streets to overthrow Tsar Nicholas II.

The reason more Russians haven’t risen up against Putin is that he has given them something they have not had for a very long time, something more valuable to many than money or even freedom: a belief in their Russian greatness and a sense of national mission.

Putin and Dostoyevsky

In his speeches in recent years, he often quotes 19th and 20th-century Russian messianic philosophers such as Vladimir Solovyev, Nikolai Berdyaev, and Ivan Ilyin, who were themselves directly influenced by a brand of nineteenth-century Russian nationalism popularized by nineteenth-century writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a writer whom Putin has called one of his favorites.

“Our people,” Dostoyevsky wrote, “are infinitely higher, more noble, more honest, more naïve, more capable, and full of a different, very lofty Christian idea, which Europe with her sickly Catholicism and stupidly contradictory Lutherism, does not even understand.” He hailed the Russian people as the world’s bastion of truth and morality, and he lambasted Western-leaning and the radical Russian intellectuals who followed them as corrupt and disconnected from the values of their own people.

He argued that only Russia, by presiding over a Pan-Slavic empire following the principles of Orthodox Christianity, could save a spiritually bankrupt modern civilization. Russia’s mission, he wrote in 1881, the year he died, was “the general unification of all the people of all tribes of the great Aryan race.”

We hear clear echoes of this Dostoyevsky rhetoric in Putin’s own language. In a television interview he gave in 2014, just before his annexation of Crimea, he said, “There are enough forces in the world that are afraid of our strength, our ‘massiveness,’ as one of our sovereigns said. So they seek to divide us into parts.” In his 2021 essay on the history of Ukraine, Putin drew on this same logic to explain why a separate Ukrainian state is an existential threat to Russia: “The formation of an ethnically pure Ukrainian state, aggressive towards Russia, is comparable in its consequences to the use of weapons of mass destruction against us.”

Listening to similar rhetoric repeated in Putin’s address to the parliament on February 21, 2022, a few days before Russian tanks crossed the Ukrainian border, you’d hardly guess that it was 2022 and Russia has invaded Ukraine. You’d think that it was 1941 and Hitler had just attacked or was about to, or even 1812 as Napoleon crossed the Nieman River to invade Russia. Both of these events remain firmly rooted in Russian national consciousness to this day, which is one reason why Putin’s xenophobic words find such resonance among the majority of the Russian public.

If so many Russians are willing to believe the state-issued lie that the war in Ukraine is a peacekeeping mission to “de-Nazify” a country that, under Western influence, is indiscriminately liquidating Russian citizens, that is only because this cultural script runs deep in Russian history.

Putin’s Psychology, Russia’s Psychology

Fear of foreigners runs deep in Putin’s own blood. One of his brothers died of diphtheria during the Nazi siege of Leningrad in World War II. His maternal grandmother was killed by the Germans in that war. And his maternal uncles disappeared at the front without a trace. Putin’s personal hurts and anxieties go further still. One evening in December 1989, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when he was serving in East Berlin as a KGB agent, mobs roamed the streets near the agency’s headquarters.

Fearing for his life, the thirty-seven-year-old Putin begged Moscow to do what Moscow had always done in the face of popular uprisings: send in military reinforcements. The reinforcements never came. “Moscow is silent,” is the response he received from a fellow officer. As he and his comrades tensely watched democratic forces sweep across Europe, he experienced first-hand the failure of a weakened Soviet empire to protect its own citizens abroad.

That night, perhaps more than any moment, was the initial catalyst for Putin’s extreme sensitivity to the perceived existential threat facing Russians in a post-Soviet world.

Given Russia’s past and Putin’s biography, then, his need to assert Russian strength in a hostile world makes perfect sense. No wonder he once called the fall of the Soviet Union “a major geopolitical disaster of the century,” going on to say that, “as for the Russian nation, it became a genuine drama. Tens of millions of our co-citizens and compatriots found themselves outside Russian territory. Moreover, the epidemic of disintegration infected Russia itself.”

For the rest of his career, Putin would play the role of savior of his people by ridding Russia of the infection eating away at the country from within—corruption and economic turmoil that he insists are caused by the West—and threatening millions of Russian citizens abroad.

To call Putin’s actions right now unhinged is to misunderstand the psychology of both the man and the country he leads. In his world view, shelling Ukrainian civilians and instituting something akin to martial law at home are rational, necessary steps he must take to protect his people, re-establish hegemony, and lead Russia to victory in her perennial battle against the West.

And that battle, alas, can be traced back to the writings of Dostoyevsky, even if Putin has taken the nineteenth-century author’s nationalism to a whole new, virulent level unimagined by the writer.

Yet ideas tend to take on a life of their own, and Dostoyevsky, alas, has helped inspire the fervent, messianic nationalism that Putin has so effectively adopted in service of bloodier goals.

***

Connect with Dr. Kaufman on Amazon, Twitter, Facebook, his private FB Group, Linked In, Instagram, Goodreads, and YouTube, and sign up for his newsletter here.

Follow Books Behind Bars on Twitter and Facebook.

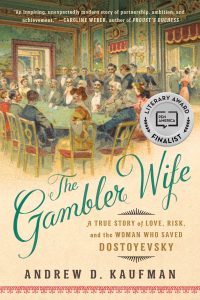

Order The Gambler Wife: A True Story of Love, Risk, and the Woman Who Saved Dostoyevsky

A PEN/America finalist, now optioned for film!

With great respect to you and your great work on exosomes, and exposing the (non-existent) virus deception and all it’s terrible harms, I must inform you that the modern history of Ukraine is a history created and prosecuted by the USA (mainly) and latterly the UK and Europe. There is plenty I can share but I think the most useful advice I can give would be to suggest you watch this film by Oliver Stone – Ukraine on Fire. ( https://www.bitchute.com/video/l7n6nBoJ6nMS/ ).

With best wishes

Nick